A House is a House

Georgia Howe on ‘Pemi Aguda’s story collection Ghostroots

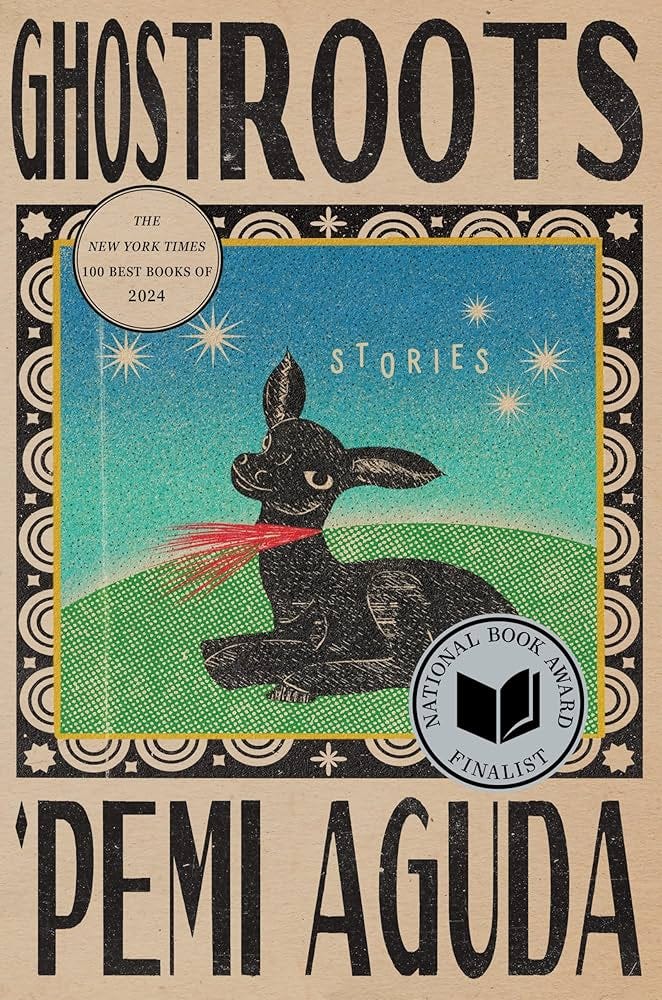

“This is the first pimple of your life,” begins ‘Pemi Aguda’s story collection, Ghostroots. Set in the author’s home city of Lagos, Nigeria, Ghostroots contains twelve short stories, all permeated by an impression that something sinister dwells just beneath the skin of each story––that something awful is going to burst from the text.

Ghostroots is a masterclass in genre bending and blending. Aguda’s stories vacillate between horror, magical realism, and folklore, tied together by a discomforting unreality. Existing in the liminal space between genres, Aguda disrupts readers’ preconceived notions of perspective, meaning, narrative, and form.. Ghostroots utilizes narrators of varying genders, class, and familial relationships to capture the diversity of experience of a culture (see similar in How to Love a Jamaican by Alexia Arthurs). Each story is heavily steeped in the uncanny, shaped by wicked humans and hauntings that are reminiscent of Shirley Jackson. The collection is captured perfectly by its title; rooted in place and colored by something immaterial and inhuman.

There are several standouts in Ghostroots, each unique in style and subject. The opening story, “Manifest,” follows a young woman’s descent into a state of compulsive evil, mirroring that of her late grandmother. The subsequent violence is horrific, yes, but not reliant on gore. Rather, Aguda simply forces the reader to sit in the shocking sin of it all. “Manifest” is written in second person point of view, implicating the reader in each despicable act whether they like it or not. Aguda asks uncomfortable questions: do we inherit the wickedness of our ancestors? Is wickedness learned, or can it simply manifest, uncalled, in our blood? There is no answer in “Manifest.” Only a mirror that reflects what dwells in the worst parts of ourselves.

Aguda’s ability to write in the in-between shines in “The Hollow.” The story follows a young architect named Arit during her attempt to map a house for renovations. The house, however, would prefer to unfold itself through time and space. It is constantly transforming, defying Arit’s attempts to pin it down on paper with measurements. The narrative flashes back through generations, concurrently following a string of women who experience violence at the hands of men. The house becomes an entity of its own and swallows the male perpetrators away into nothingness, their bodies simply disappearing into the ever-changing walls and floors. Here, Aguda delivers karmic justice upon violent abusers, silencing them whether the women they abuse want it or not.

What sets “The Hollow” apart from the rest of Ghostroots is its deep and profound exploration of a singular idea: the home. The house is not only a magical, physical entity in this tale. It is a symbol of multiple, conflicting ideas. Aguda shows the reader that a house––that thing that is at once a physical space and a site rife with metaphor––will never be one thing. Short paragraphs flow in and out of poetic refrains that all ask the same question: what is a house? Aguda offers many answers, each true to a different inhabitant of the house at a different time. A house is a pressure cooker. An escape. A prison. A history.

Aguda’s endings are contentious. Her works are short and some, like “Contributions,” span only a few pages. Many of her stories follow characters who descend into pain, terror, or chaos, and then end without any real resolution of the plot. Aguda does not tie up loose ends in a satisfying bow, nor does she rely on cliff-hanging shock. She leaves readers sitting in the discomfort of the narrative, like a diminished chord is never resolved. This choice has many readers decrying Ghostroots as abrupt and dissatisfying, complaining that each story was cut too short. But that exact feeling of discomfort that the endings create is what plagues her uncanny characters. Aguda forces her readers to remain haunted by her stories long after they’ve put down her book.

A 2024 National Book Award finalist, Ghostroots is a book about many things, from motherhood, to justice, to haunting, to culture. Yet, across subject, genre, and form, Aguda is asking questions about home. What dwells within you, and what do you dwell within? This returns us to the final paragraph of “The Hollow”: “A house is a pot, a house is a bag, a house is a prison, a house is a justification, a house is a child on your back, weighing you down. A house is a house, and you can erase it, wreck it, tear it to the ground. A house is a house, and no, you can never forget, but you can walk away.”

Georgia Howe (she/her) is a Maine-based creative with a BFA in Creative Writing from Emerson College. She loves exploring folklore and stories from the woods through a queer and gendered perspective. Along with a number of published articles and short stories, her past work includes creative production for INDEX Magazine as well as editorial work for a number of literary and arts magazines. You can also find Georgia painting, reading fairy tales, baking danishes, or on Instagram at @georgia_howe